Introduction

As the Kingdom of Eswatini plans to deal with the consequences of pro-democracy protests and the continued calls for the establishment of a national dialogue seemingly going unanswered, it may be an opportune time to examine what type of national dialogue would benefit the country. It has been over a year since King Mswati III agreed to the Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) leaders’ proposal to ensure conditions are conducive for setting up a national dialogue. National dialogues are becoming an increasingly popular tool for conflict resolution, and in the case of Eswatini, political transformation. In recent years, we have witnessed several attempts to conduct national dialogues as critical tools in the prevention of conflict and for managing political crises and transitions in the SADC region. By agreeing to undertake this political process, it increases the potential for a more meaningful engagement as it increases participation beyond that of the political elites, while also creating a platform for deeper discussions to formulate solutions to the crisis. This paper examines and proposes the type of national dialogue best suited to bring together the conflicting parties and bring an end to the political protests and violence.

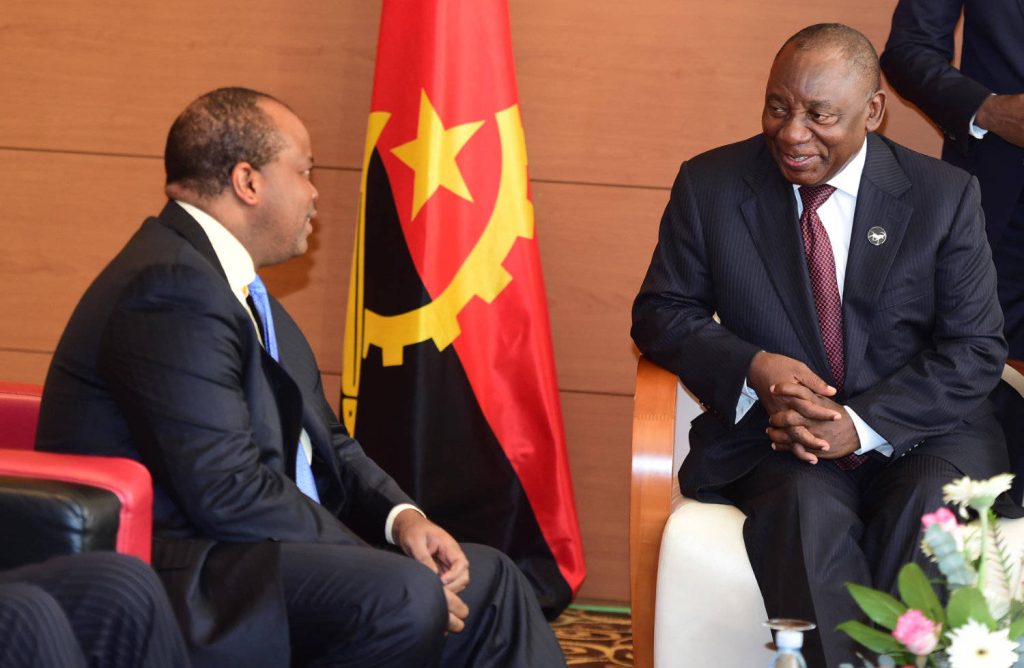

Photo: GCIS

Understanding National Dialogues

National dialogues can be defined as ‘nationally owned political processes aimed at generating consensus among a broad range of national stakeholders in times of deep political crisis, in post-war situations or during far-reaching political transitions’.1Berghof Foundation (2017) ‘National Dialogue Handbook A Guide for Practitioners’, Available at: <https://www.jointpeacefund.org/files/documents/berghof_foundation-national_dialogue_handbook.pdf> (Accessed: 24 November 2022). They may also be defined as broad-based, inclusive, and participatory negotiation platforms involving all sectors of society brought together to negotiate and strengthen the social contract between citizens and the state.

Agreeing on the objectives of a national dialogue may seem like a straightforward exercise, but if the foundation is not correctly laid, unforeseen fissures may appear to the detriment of the process. However, while there may be wide-ranging inclusive buy-in among the different stakeholders, there remain three inherent tensions when designing national dialogue processes that may influence their legitimacy and effectiveness:

- Size and composition: Agreeing on the number of participants and deciding on the size of the inclusion net and the relevant representatives to be included.

- Power and mandate: Relationship to existing state institutions – parliaments and governments and what their decision-making powers are.

- Independence: Whether national dialogue decisions should be ratified by existing institutions or be final. Legitimacy deficits should be considered.2Papagianni, Katia (2016) ‘Civil Society Dialogue Network Discussion Paper No. 3 National Dialogue Processes in Political Transitions’, Available at: <https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/176342/National-Dialogue-Processes-in-Political-Transitions.pdf> (Accessed: 24 November 2022).

Sporadic protests have continued to flare up for the past year and a half. Eswatini has witnessed numerous protests which have spiralled into widespread rioting, causing extensive destruction and claims of the deaths of several protestors shot by security forces while calling for democratic reforms. It was this violence which prompted regional leaders to seek appropriate response measures to address the developing political crisis.

During his last working visit to Eswatini in November 2021, President Cyril Ramaphosa, as Chairperson of the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation, had an audience with King Mswati III to discuss the establishment and parameters of a national dialogue. Ramaphosa’s visit followed several regional summits and fact-finding missions, including exploratory visits from SADC Special Envoys. According to a press release, Ramaphosa and the King held discussions on several issues relating to the political and security situation in Eswatini. A key takeaway from the deliberations was a resolution that the kingdom ‘will embark on a process that will work towards the establishment of a National Dialogue forum.’3The Presidency, South Africa (2021) ‘Statement by Chair of SADC Organ Troika on engagement with His Majesty King Mswati III of Eswatini’, Available at: <https://www.thepresidency.gov.za/press-statements/statement-chair-sadc-organ-troika-engagement-his-majesty-king-mswati-iii-eswatini> (Accessed: 24 November 2022).

Photo: Bernard Gagnon

Eswatini’s political opposition, under the umbrella of the Multi-stakeholder Forum (MSF),4The MSF comprises political parties under the Political Parties Assembly and civil society organisations representing democracy, governance and leadership, women, youths, church, labour, people living with disabilities, and business. has warned the regional organisation to refrain from ‘reinventing the wheel’ when engaging with the King and his government. In a statement, the MSF warned that King Mswati III is delaying the commencement of a national dialogue and that regional leaders should not be misled by the inaction of the King. The MSF stated:

The issue affecting the nation is more than just a security concern; it is fundamentally a political question. The security issue arises from the political problem, which is the lack of and absence of democratic governance in the country. The security issue can and will never be resolved without addressing the political question … The security instability is but a symptom of a sickness of our politics. SADC cannot resolve the Swaziland crisis by addressing symptoms and not the crux of the crisis.5Daily Maverick (2022) ‘King Mswati accused of delaying Eswatini national dialogue’, 4 September, Available at: <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-09-04-king-mswati-accused-of-delaying-eswatini-national-dialogue> (Accessed: 24 November 2022).

To expedite and assist with the facilitation of a national dialogue forum, Ramaphosa and the King agreed that the SADC Secretariat will, in collaboration with the government, draft the Terms of Reference (ToRs) for the forum. This process is important as it will clarify issues such as:

- The composition of the forum;

- Incorporating structures and processes enshrined in the Constitution;

- The role of Parliament;

- The role of the Sibaya – a traditional gathering called by the King to consult his subjects – to be used as the format for the national dialogue forum; and

- Confirmation of timelines and/or milestones.

While this was all agreed to, the planning process has stalled. It appears that Mswati and the political opposition cannot agree on the platform for the dialogue. Mswati has insisted it should take the format of a Sibaya, a traditional consultation as enshrined in Eswatini’s Constitution.6Constitutions Project (2023) Eswatini’s Constitution of 2005, Available at: <https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Swaziland_2005.pdf?lang=en> (Accessed: 13 June 2023). The opposition leaders have rejected using the Sibaya format, saying it is not a conducive mechanism for dialogue but rather promotes monologue. If adopted, this process will be managed by the palace officials and held in an environment where the King talks down to his subjects rather than seeking to elicit their views.

Instead, the opposition has called for the process to be coordinated by a neutral body with the inclusion of all stakeholders, as well as banned opposition political parties. In their November meeting, Ramaphosa and the King agreed that a Sibaya could be part of the process. To mitigate this term of the agreement, the SADC later stated that the dialogue should be much more representative and include banned political parties.

Earlier in February 2022, the SADC drafted a framework for a multi-stakeholder national dialogue. Included in the draft framework was a timetable for a national dialogue, which was to commence in April. As it stands, no progress appears to have been made in establishing the process. After that, Mswati missed two SADC summits to discuss how to kickstart the dialogue.

Photo: UN/Cia Pak

Types of National Dialogues

When planning the conditions for the national dialogue, it is important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all model. As stated above, national dialogues will have a higher chance of success if they are inclusive, which in the case of Eswatini, must be transparent and allow for public participation, a neutral and credible convener or mediator, and an implementation plan. According to the National Dialogue Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners,the objectives of national dialogues tend to be context dependent: ‘They may focus on a narrower set of specific or substantive objectives (i.e. security arrangements, constitutional amendments, truth commissions, etc.), or on broad-based change processes, which may entail (re)building a (new) political system and developing a (new) social contract.’7Berghof Foundation (2017) op. cit. It is for the emaSwati stakeholders to decide and agree on the objective before the process commences. If this part of the process is not carefully considered, it may result in mistrust, fear, negative agenda setting, etc.

The Handbook distinguishes between two main types of national dialogue, identified according to the function they seek to fulfil. Each one is discussed below.

National Dialogues as Mechanisms for Crisis Prevention and Management

- A shorter-term endeavour undertaken strategically to resolve or prevent the outbreak of armed violence.

- Key aims: Breaking political deadlocks and re-establishing political consensus, while further reform and steps toward change can be negotiated.

- Key characteristics: Tend to be smaller in size and shorter in duration with more limited mandates. They are often easier to manage due to the restricted number of actors involved. They may reflect a less inclusive structure, whereby broad-based societal buy-in for desired changes can be difficult to generate.

National Dialogues as Mechanisms for Fundamental Change

- Efforts with a longer-term trajectory envisioned to redefine state-society relations or establish a new ‘social contract’.

- Key aims: Far-reaching institutional and constitutional changes.

- Key characteristics: Broad mandate and often significant dialogue. Seeking to include large strata of society and generate widespread support. They are confronted by the challenges of managing large-scale processes.

In the case of Eswatini, it may be better suited to adopt a more hybrid model incorporating elements from both approaches, as it may lead to a sustained political solution.

The political context in which the implementation of a national dialogue takes place has a direct impact on the success of the process. Huma Haider, an independent research consultant, lists the following as factors to be considered:

- Political will: The greater the level of political will and elite agreement on the way forward, the greater the likelihood of successful outcomes and implementation.

- Links to other transitional processes: National dialogues need to be embedded in larger change processes to promote real structural change. If disconnected from other political processes, such as constitution-making, they are likely to be counter-productive.

- Common ground among parties: The absence of diametrically opposed political camps can make it more likely to arrive at a common view or shared objectives in dialogue, allowing for the process to move forward. In contrast, drastically different views can exacerbate distrust and stall the process.

- Public buy-in: Public support or lack thereof can enable or constrain progress in the national dialogue process. The degree of buy-in is influenced by the availability of public information, good communication, and media engagement – all of which affect the level of transparency and understanding of the process.

- Learning from experience: National dialogues have benefitted from dialogue expertise and learning from past national dialogues.

- The role of external actors and national ownership: Support (e.g., political, financial and technical) or resistance by external actors can influence the degree of success of national dialogues. It is important to strike a balance between external support and national ownership. The latter can increase the likelihood of public buy-in and perceptions of legitimacy and the chances of implementation.8Haider, Huma (2019) ‘National dialogues: lessons learned and success factors’, Available at: <https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/14379/543_National_Dialogues_Lessons_Learned.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y> (Accessed: 24 November 2022).

Haider also states that in conjunction with political context factors, design or process factors are also important, as these play a role in influencing the likelihood of reaching sustainable agreements. Key process factors include:

- The degree of inclusion and participation: Most literature on this subject emphasises that the transformative potential of national dialogues can only be realised if they are genuinely inclusive of society. To be truly inclusive, it is necessary to help balance power asymmetries and ensure actual decision-making power. Highly inclusive and participatory national dialogues may render discussions unwieldy, however, and make it difficult to resolve key political questions. The success of national dialogues can depend in large part on finding an equilibrium between efficiency and inclusiveness.

- Representation and selection criteria: Established selection criteria and procedures for participants in national dialogues can support or hinder the broad representation of different social and political groups. Transparency in the criteria is significant.

- Objective and scope-setting: It is important to avoid overburdening mandates and agendas. It can be challenging to balance the breadth of the mandate with efficiency and independence. While a narrower mandate can be more manageable and efficient, it can limit the room for change and may contribute to the persistence of an elite-led process. Clarity and relevance to local populations are key characteristics to adopt in deriving a suitable mandate and agenda. Addressing development issues and peace dividends at the outset can be important to the success of national dialogues.

- Institutional framework and support structures: A comprehensive support structure of important actors close to competing parties can help participants to be prepared (with the necessary expertise and tools) to compromise and to build coalitions, allowing them time to agree on common positions. Such structures do not, however, necessarily improve the quality of participation or guarantee implementation.

- Role of authority figures: A credible, broadly accepted, independent, respected, and charismatic convenor, mediator or facilitator can significantly affect the strength of the national dialogue, indicating seriousness and trust in the process.

- Decision-making procedures: These procedures enable or constrain the ability of national dialogues to reach an agreement and implement it. While consensus can help expand agendas and include often excluded voices, an inability to reach consensus can benefit the more established forces, as the absence of progress can mean preserving the status quo. Consensus-based decision-making needs to be complemented by other pragmatic mechanisms where deadlocks can be broken, such as through the use of working groups.

- Confidence-building measures: National dialogues must be accompanied by a series of steps to attenuate tensions, to establish a level of ‘working trust’ to engage in a meaningful dialogue. Trust-building is important throughout all phases to ensure agreements are implemented.

- Provision for implementation: It is necessary to ensure that sufficient funds for implementation, expertise and accountability mechanisms are in place, such that key actors may feel bound by what has been agreed. Transitional bodies and/or new institutions are often set up to implement the outcomes. Implementation can be tough if participants have made unrealistic decisions, if political will is absent, or if external actors fail to provide necessary support.9Ibid.

It is important to emphasise that even with all the above factors in place, the process may still fail if the commitment levels from both state and non-state actors are uncertain. After some initial apprehension, both state and non-state actors may appear open to adopting a national dialogue forum which bodes well for the process. However, if Eswatini is to succeed, it may require certain difficult conditions to be agreed upon before the process commences. Agreeing to the ToRs is critical. If not properly managed, it may be a stumbling block preventing the national dialogue from starting. Otherwise, there is a possibility that the whole process may merely be a case of going through the motions without a chance of any real reforms being implemented.

Photo: GCIS

Conclusion

In short, if the national dialogue process is to succeed, the following must be taken into account:

- If there is no trust in the stakeholders, the process will fail before it starts.

- A neutral convenor must be accepted by all parties.

- The process must be insulated from undue political or external influence.

- Insisting on transparency at all levels of the process is critical.

- Outcomes from the process must be acted upon and directed to their relevant streams – policy, legislation, or strategy.

Moving forward, the conveners and participants of the Eswatini national dialogue forum should keep in the front of their minds that: ‘Even in the most successful instances, national dialogue is but one step along the long and arduous path of building a peaceful society.’10Stigant, Susan and Murray, Elizabeth (2015) ‘National Dialogues: A Tool for Conflict Transformation?’ Available at: <https://www.usip.org/publications/2015/10/national-dialogues-tool-conflict-transformation> (Accessed: 24 November 2022). While King Mswati has stalled the process, the SADC and its leaders should encourage him to adhere to his earlier commitment to establish a national dialogue forum to heal the nation. In the interim, the SADC should compel the King and opposition leaders to call on all stakeholders to collaborate in ending the reoccurrence of violence and maintaining peace in the country as efforts to commence work on the national dialogue forum proceeds. Mswati should not use delaying tactics to extend his undemocratic rule as it does not bode well for the process and may limit the chances of holding a successful national dialogue forum. The SADC and its leaders should impress upon Mswati that it is in the best interests of the nation and the national dialogue process moving forward should be seen as a positive stakeholder engagement rather than seemingly preferring to hold the dialogue on his own terms. If not, the national dialogue forum may fail before it has started.

Dr Craig Moffat is a visiting senior research fellow at NUPI.